Leader Who Rose to Power After the French Revolution and Patron of the Arts

Chapter 3: Political Ideologies and Movements

Afterward the Revolution

The French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars greatly shook Europe. The French Revolution was seen by the European great powers as both threatening and, as it progressed and radicalized, morally repulsive, but at to the lowest degree it had largely stayed confined to France. From the perspective of elites, Napoleon'due south conquests were even worse because everywhere the French armies went the traditional club of society was overturned. French republic may have been the greatest economic casher, only Napoleon's Italian, German, and Polish subjects (among others) also had their first taste of a society in which ane'southward status was not defined by birth. The kings and nobles of Europe had skilful cause to fear that the fashion of life they presided over, a social order that had lasted for roughly ane,000 years, was disintegrating in the class of a generation.

Thus, after Napoleon's defeat, in that location had to be a reckoning. Merely the about stubborn monarch or noble thought it possible to completely disengage the Revolution and its effects, but there was a shared want among the traditional elites to re-establish stability and social club based on the political system that had worked in the past. They knew that there would have to be

some

concessions to a generation of people who had lived with equality under the police force, simply they worked to reinforce traditional political structures while but granting limited compromises.

Conservatism

That being noted, how did elites empathize their own role in order? How did they justify the power of kings and nobles over the bulk of the population? This was not but about wealth, subsequently all, since there were many non-noble merchants who were as rich, or richer, than many nobles. Nor was it viable for most nobles to merits that their rights were logically derived from their mastery of warfare, since only a pocket-size percent of noblemen served in royal armies (and those that did were not necessarily very good officers!). Instead, European elites at the time explained their own social function in terms of peace, tradition, and stability. Their credo came to exist called conservatism: the idea that what had worked for centuries was inherently better at keeping the peace both within and between kingdoms than were the forces unleashed by the French Revolution.

Conservatism held that the one-time traditions of rule were the best and most desirable principles of government, having proven themselves relatively stable and successful over the class of 1,000 years of European history. It was totally opposed to the idea of universal legal equality, let lone of suffrage (i.due east. voting rights), and it basically amounted to an endeavor to maintain a legal political hierarchy to go along with the existing social and economic hierarchy of European society.

The central statement of conservatism was that the French Revolution and Napoleon had already proved that too much modify and innovation in politics was

inherently

destructive. According to conservatives, the French Revolution had started out, in its moderate stage, by arguing for the primacy of the mutual people, but it quickly and inevitably spun out of control. During the Terror, the male monarch and queen were beheaded, French society was riven with bloody disharmonize, tens of thousands were guillotined, and the revolutionary government launched a blasphemous crusade confronting the church. Napoleon'due south takeover – itself a symptom of the anarchy unleashed past the Revolution – led to near twenty years of war and turmoil across the map of Europe. These events

proved

to conservatives that while careful reform might exist adequate, rapid alter was not.

Many conservatives believed that human nature is basically bad, evil, and depraved. The clearest argument of this idea in the early nineteenth century came from Joseph de Maistre, a conservative French nobleman. De Maistre argued that homo beings are not aware, non least because (as a staunch Catholic), he believed that all human souls are tainted by original sin. Left unchecked, humans with too much liberty would e'er indulge in depravity. Only the allied forces of a stiff monarchy, a strong nobility, and a potent church could agree that inherent evil in check. It is worth noting that De Maistre wrote outside of French republic itself during the revolutionary menstruum, first in the modest Italian kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (he was a noble in both French republic and Piedmont) and then in Russia. His bulletin resonated strongly with the curvation-bourgeois Russian Tsar Alexander I in particular.

A more businesslike conservative take was exemplified by a British lord, Edmund Burke. He argued that, given the complexity and fragility of the social cloth, just the force of tradition could forbid political anarchy. As the French Revolution had demonstrated, gradual reforms had the effect of unleashing a tidal wave of pent-upwardly anger and, more to the point, foolish decisions by people who had no experience of making political decisions. In his famous pamphlet

Reflections On The Revolution in France

, he wrote "Information technology is said that twenty-four millions ought to prevail over two hundred thousand. True; if the constitution of a kingdom be a problem of arithmetic." To Burke, the common people were a mob of uneducated, inexperienced would-be political decision-makers and had no business trying to influence politics. Instead, information technology was far wiser to keep things in the basic form that had survived for centuries, with minor accommodations equally needed.

Burke was an eminently applied, businesslike political critic. De Maistre's ideas may have looked back to the social and political thought of past centuries, just Burke was a very grounded and realistic thinker. He simply believed that "the masses" were the concluding people i wanted running a government, because they were an uneducated, uncultivated, uncivilized rabble. Meanwhile, the European nobility had been raised for centuries to rule and had developed both cultural traditions and systems of teaching and grooming to form leaders. It was a given that not all of them were very good at it, simply co-ordinate to Burke there was simply no comparison between the class of nobles and the class of the mob – to let the latter rule was to invite disaster. And, of course, conservatives had all of their suspicions confirmed during the Terror, when the whole social order of France was turned upside down in the name of a perfect society (Burke himself was particularly aggrieved past the execution of the French Queen Marie Antoinette, whom he saw every bit a perfectly innocent victim).

Early nineteenth-century conservatism at its best was a coherent critique of the violence, warfare, and instability that had accompanied the Revolution and Napoleonic wars. In practice, however, conservatism all too frequently degenerated into the stubborn defense of corrupt, incompetent, or oppressive regimes. In turn, despite the practical impossibility of doing so in near cases, in that location were real attempts on the part of many conservative regimes after the defeat of Napoleon to completely turn dorsum the clock, to try to sweep the reforms of the revolutionary era under the collective carpeting.

One boosted conservative figure who lived a generation later on than Shush and De Maistre deserves particular attending: the French aristocrat Arthur de Gobineau (1816 – 1882). By the time Gobineau was an adult, the earlier versions of conservatism seemed increasingly outdated, specially De Maistre's theological claims regarding original sin. Gobineau chose instead to prefer the language of the prevailing form of intellectual authority of the later nineteenth century: scientific discipline. From 1853 to 1855 he published a series of volumes collectively entitled Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. The Essay claimed that the European dignity had once been an unsullied "pure" example of a superior race rightfully ruling over social inferiors who were born of lesser racial stock. Over time, withal, the nobility had foolishly mixed with those inferiors, diluting the precious racial characteristics that had sustained noble rule. Besides, by conquering the Americas and parts of Africa and Asia, Europeans every bit a whole undermined their "purity" and hence their superiority to non-Europeans.

The Essay 's power to persuade was in large office because Gobineau claimed that his arguments were "scientific." In debates with his friend and patron Alexis de Tocqueville, one of the major intellectual voices of liberalism, Gobineau asserted that he was but describing reality past pointing out that some people were racially superior to others. Needless to say, Gobineau's claims were nonsense in terms of actual scientific reality, but by using the language of scientific discipline Gobineau's grandiose celebration of racial hierarchy served to back up the dominance and wealth of those already in power behind a facade of a "neutral" assay.

Gobineau's work was enormously influential over fourth dimension. It would inspire the Social Darwinist movement that arose later in the nineteenth century that claimed that the lower classes were biologically inferior to the upper classes. It would be eagerly taken up by anti-Semites who claimed that Jews were a "race" with inherent, destructive characteristics. In the twentieth century information technology would directly inspire Nazi ideology likewise: Hitler himself cited Gobineau in his own musings on racial hierarchy. Thus, Gobineau represents a transition in nineteenth-century conservatism, away from the theological and tradition-leap justifications for social hierarchy of a De Maistre or Burke and towards pseudo-scientific claims about the supposed biological superiority of some people over others.

Ideologies

Post-obit Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, conservatives faced the daunting task of not merely creating a new political order but in holding in check the political ideologies unleashed during the revolutionary era: liberalism, nationalism, and socialism. Enlightenment thinkers had get-go proposed the ideas of social and legal equality that came to fruition in the American and French Revolutions. Likewise, the course of those revolutions forth with the work of thinkers, writers, and artists helped create a new concept of national identity that was poised to accept European politics by storm. Finally, the political, social, and economic chaos of the turn of the nineteenth century (very much including the Industrial Revolution) created the context out of which socialism emerged.

An "ideology" is a set of beliefs, often having to do with politics. What is the purpose of government? Who decides the laws? What is but and unjust? How should economics function? What should be the office of organized religion in governance? What is the legal and social condition of men and women? All of these kinds of questions have been answered differently from civilization to civilisation since the primeval civilizations. In the nineteenth century in Europe, a handful of ideologies came to predominate: conservatism, nationalism, liberalism, and socialism. In turn, briefly put, 3 of those ideologies had 1 affair in mutual: they opposed the fourth. For the first half of the nineteenth century, socialists, nationalists, and liberals all agreed that the bourgeois order had to be disrupted or fifty-fifty dismantled entirely, although they disagreed on how that should be accomplished and, more importantly, what should supplant it.

Romanticism

Even before the era of the French Revolution, the seeds of nationalism were planted in the hearts and minds of many Europeans as an attribute of the Romantic movement. Romanticism was not a political movement – it was a movement of the arts. It emerged in the tardily eighteenth century and came of age in the nineteenth. Its central tenet was the idea that there were cracking, sometimes terrible, and literally "awesome" forces in the universe that exceeded humankind'southward rational ability to understand. Instead, all that a human existence could exercise was attempt to pay tribute to those forces – nature, the spirit or soul, the spirit of a people or civilisation, or fifty-fifty expiry – through art.

The key themes of romantic art were, first, a profound reverence for nature. To romantics, nature was a vast, overwhelming presence, against which humankind's activities were ultimately insignificant. At the same time, romantics celebrated the organic connection between humanity and nature. They very often identified peasants as being the people who were "closest" to nature. In turn, information technology was the chore of the artist (whether a writer, painter, or musician) to somehow gesture at the profound truths of nature and the human spirit. A "true" artist was someone who possessed the real spark of creative genius, something that could non exist predicted or duplicated through grooming or education. The point of art was to let that genius emanate from the work of art, and the result should be a profound emotional experience for the viewer or listener.

Quite by blow, Romanticism helped plant the seeds of nationalism, cheers to its ties to the folk movement. The central thought of the folk motility was that the essential truths of national character had survived among the common people despite the harmful influence of then-called civilization. Those folk traditions, from folk songs to fairytales to the remnants of pre-Christian pagan practices, were the "truthful" expression of a national spirit that had, supposedly, laid dormant for centuries. By the early eighteenth century, educated elites attracted to Romanticism set up out to gather those traditions and preserve them in service to an imagined national identity.

The iconic examples of this phenomenon were the Brothers Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm, who were both expert philologists and avid collectors of German folk tales. The Brothers Grimm nerveless dozens of folk ("fairy") tales and published them in the commencement definitive collection in German. Many of those tales, from Sleeping Dazzler to Cinderella, are best known in American culture thanks to their adaptation as animated films by Walt Disney in the twentieth century, just they were famous already past the mid-nineteenth. The Brothers Grimm also undertook an enormous project to compile a comprehensive German dictionary, not only containing every German word but detailed etymologies (they did not live to run across its completion; the 3rd volume E – Forsche was published shortly before Jacob's decease).

The Grimm brothers were the quintessential Romantic nationalists. Many Romantics like them believed that nations had spirits, which were invested with the core identity of their "people." The point of the Grimm brothers' work was reaching back into the remote by to grasp the "essence" of what information technology meant to be "German." At the time, in that location was no state chosen Germany, and yet romantic nationalists similar the Grimms believed that there was a kind of German soul that lived in old folk songs, the German language language, and German traditions. They worked to preserve those things earlier they were further "corrupted" by the modernistic world.

In many cases, romantic nationalists did something that historians later called "inventing traditions." Ane iconic example is the Scottish kilt. Scots had worn kilts since the sixteenth century, only there was no such thing as a specific color and pattern of plaid (a "tartan") for each family or association. The British regime ultimately assigned tartans to a new class of soldier recruited from Scotland: the Highland Regiments, with the wider identification of tartan and clan only emerging in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. The point was instilling a nationalist pride in a specific group of military recruits, not celebrating an "authentic" Scottish tradition. Likewise, in some cases folk tales and stories were simply made up in the name of nationalism. The keen epic story of Finland, the Kalevala , was written by a Finnish intellectual in 1827; it was based on actual Finnish legends, merely it had never existed equally one long story before.

The bespeak is not, withal, to emphasize the falseness of the folk movement or invented traditions, but to consider

why

people were so intent on discovering (and, if necessary, inventing) them. Romanticism was, among other things, the search for stable points of identity in a changing world. Likewise, folk traditions – even those that were at least in part invented or adapted – became a way for early on nationalists to identify with the civilization they now connotated with the nation. It is no coincidence that the vogue for kilts in Scotland, ones now identified with clan identity, emerged for the first time in the 1820s rather than earlier.

Nationalism

Romantic nationalism was an integral function of actual nationalist political movements, movements that emerged in hostage in the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic wars. Those movements would ultimately succeed in seeing their goals realized nearly without exception, although that procedure took over a century in some cases (as in Poland and Ireland). Central to nationalist movements was the concept that the state should correspond to the identity of a "people," although who or what defines the identity of "the people" proved a vexing issue on many occasions.

The discussion of nationalism starts with the French Revolution, because more than any other outcome, information technology provided the model for all subsequent nationalisms. The French revolutionaries declared from the outset that they represented the whole "nation," not but a certain part of it. They erased the legal privileges of some (the nobles) over others, they made faith subservient to a secular authorities, and when threatened by the conservative powers of Europe, they called the whole "nation" to arms. The revolutionary armies sang a national canticle, the Marseillaise, whose lyrics are as warlike as the American equivalent. Central to French national identity in the revolutionary catamenia was fighting for la patrie , the fatherland, in place of the old allegiance to king and church building.

The irony of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, still, was that the countries invaded past the French somewhen adopted their ain nationalist beliefs. The invaded countries turned the democratic French principle of self-determination into a sacred right to defend their ain national identities, shaped by their own detail histories, confronting the universalist pretensions of the French. That was reflected in the Spanish revolt that began in 1808, the revival of Austria and Prussia and their struggles of "liberation" against Napoleon, Russia's leadership of the anti-Napoleonic coalition that followed, and vehement British pride in their defiance to French military pretensions.

Nationalisms Across Europe

As the Napoleonic wars drew to a close for the first time in 1814, the smashing powers of Europe convened a gathering of monarchs and diplomats known as the Congress of Vienna, discussed in detail in the next chapter, to deal with the backwash. That coming together lasted months, thanks in role to Napoleon's inconvenient render from Elba and last stand at Waterloo, but in 1815 it concluded, having rewarded the victorious kingdoms with territorial gains and restored conservative monarchs to the thrones of states like Spain and French republic itself. Cypher could take mattered less to the diplomatic representatives present at the Congress of Vienna than the "national identity" of the people who lived in the territories that were carved up and distributed like pieces of cake to the victors – the inhabitants of northeastern Italian republic were now subjects of the Austrian rex, the entirety of Poland was divided between Russian federation and Prussia, and Smashing United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland remained secure not merely in its growing global empire, but in its possession of the entirety of Ireland.

Thus, many of Europe'due south peoples found themselves without states of their own or in states squeezed between the dominant powers of the fourth dimension. Among the notable examples are the Italians and the Poles. Italy had suffered from the domination of ane great ability or another since the Renaissance; after 1815 information technology was the Austrians who were in control of much of northern Italy. Poland had been partitioned between Austria, Prussia, and Russia in the eighteenth century, but vanishing from the map in the process. Germany, of course, was not united; Prussia and Republic of austria vied with each other for say-so of the German lands, only both were fundamentally conservative powers uninterested in "High german" unification until later in the century.

What had changed, even so, was that the language of nationalism and the idea of national identity had come up into its own by the late Napoleonic period. For example, German nationalism was powerful and popular after the Napoleonic wars; in 1817, simply two years after the end of the Congress of Vienna, German nationalists gathered in Wartburg where Martin Luther had commencement translated the Bible into German language, waving the blackness, red, and gold tricolor flag that would (over a century later) become the official flag of the German nation. Two years after, a nationalist poet murdered a conservative 1, and the Austrian Empire passed laws that severely limited freedom of speech, specifically to comprise and restrict the spread of nationalism. Despite this effort, and the Austrian clandestine police, nationalism continued to spread, culminating in a big and self-consciously nationalistic movement seeking German unity.

The 1830s were a pivotal decade in the spread of nationalism. The Italian nationalist leader Giuseppe Mazzini founded Young Italy in 1831, calling for a "springtime of peoples" in which the people of each "nation" of Europe would topple conservative monarchs and assert their sovereignty and independence. That movement would quickly spread beyond Italia: "young" became the rallying discussion and idea of nationalism. In addition to Young Italy, at that place was a Immature Germany and a Immature Ireland, among others – the thought was that all people should and would eventually inhabit nations, and that this new "youthful" manner of politics would lead to peace and prosperity for everyone. The old, outdated borders abandoned, everyone would live where they were supposed to: in nations governed by their own people. Nationalists argued that war itself could exist rendered obsolete. Afterwards all, if each "people" lived in "their" nation, what would be the betoken of territorial conflict? To the nationalists at the time, the emergence of nations was synonymous with a more perfect future for all.

Central to the very concept of nationalism in this early on, optimistic phase was the identity of "the people," a term with powerful political resonance in just about every European language: das Volk, le peuple, il popolo, etc. In every instance, "the people" was idea to exist something more than important than only "those people who happen to live here." Instead, the people were those tied to the soil, with roots reaching back centuries, and who deserve their own government. This was a greatly romantic idea because information technology spoke to an essentially emotional sense of national identity – a sense of camaraderie and solidarity with individuals with whom a given person might not actually share much in common.

When scrutinized, the "real" identity of a given "people" became more difficult to discern. For instance, were the Germans people who speak German, or who lived in Key Europe, or who were Lutheran, or Catholic, or who think that their ancestors were from the aforementioned expanse in which they themselves were born? If united in a German nation, who would lead it – were the Prussians or the Austrians more authentically High german? What of those "Germans" who lived in places like Bohemia (i.e. the Czech lands) and Poland, with their own growing sense of national identity? The nationalist movements of the starting time half of the nineteenth century did not need to concern themselves overmuch with these conundrums because their goals of liberation and unification were non even so achievable. When national revolutions of various kinds did occur, however, they proved difficult to overcome.

Liberalism

Nationalism's supporters tended to be members of the middle classes, including anybody from artisans to the new professional course associated with commerce and industry in the nineteenth century. Many of the same people supported another doctrine that had been spread past the Napoleonic wars: liberalism. The ideas of liberalism were based on the Enlightenment concepts of reason, rationality, and progress from the eighteenth century, but as a move liberalism came of age in the postal service-Napoleonic period; the give-and-take itself was in regular apply by 1830.

Nineteenth-century liberals were usually educated men and women, including the elites of industry, trade, and the professions every bit well every bit the middle classes. They shared the conviction that freedom in all its forms—freedom from the despotic dominion of kings, from the obsolete privilege of nobles, from economic interference and religious intolerance, from occupational restrictions and limitations of speech and assembly—could but improve the quality of club and the well-being of its members.

In something of a contrast to the abstract nature of national identity among nationalists, liberalism had straightforward behavior, all of them reflecting not but abstruse theories only the physical examples of the liberal American and French Revolutions of the prior century. Perhaps liberalism'southward most fundamental belief was that there should be equality before the law, in stark contrast to the one-time "feudal" (well-nigh a slur to liberals) guild of legally-defined social estates. From that starting point of equality, the very purpose of law to liberals was to protect the rights of each and every citizen rather than enshrine the privileges of a minority.

Whereas "rights" had meant the traditional privileges enjoyed past a given social group or manor in the past, from the king'due south sectional correct to hunt game in his forests to the peasants' right to admission the common lands, rights now came to mean a central and universal privilege that was concomitant with citizenship itself. Liberals argued that liberty of speech, of a press costless from censorship, and of religious expression were "rights" that should be enjoyed by all. Too, almost liberals favored the abolition of archaic economical interference from the state, including legal monopolies on trade (e.g. in shipping betwixt colonies) and the monopolies enjoyed past those arts and crafts guilds that remained – the "right" to engage in marketplace commutation unhindered by outdated laws was part of the liberal paradigm also.

Merely as had the French revolutionaries in the early on stage of the revolution, most liberals early on nineteenth-century liberals looked to ramble monarchy as the well-nigh reasonable and stable form of government. Constitutions should exist written to guarantee the fundamental rights of the citizenry and to define, and restrict the ability of the rex (thus staving off the threat of tyranny). Liberals besides believed in the desirability of an elected parliament, albeit one with a restricted electorate: almost universally, liberals at the time thought that voting should be restricted to those who owned meaning amounts of holding, thereby (they thought) guaranteeing social stability.

Unlike nationalists, liberals saw at least some of their goals realized in post-Napoleonic Europe. While its Bourbon monarchy was restored in French republic, there was now an elected parliament, religious tolerance, and relaxed censorship. Britain remained the most "liberal" power in Europe, having long stood every bit the model of ramble monarchy. A liberal monarchy emerged as a effect of the Belgian Revolution of 1830, and by the 1840s limited liberal reforms had been introduced in many of the smaller High german states as well. Thus, despite the opposition of conservatives, much of Europe slowly and haltingly liberalized in the period between 1815 and 1848.

Socialism

The tertiary and last of the new political ideologies and movements of the early nineteenth century was socialism. Socialism was a specific historical phenomenon built-in out of 2 related factors: get-go, the ideological rupture with the club of orders that occurred with the French Revolution, and second, the growth of industrial capitalism. It sought to address both the economic repercussions of the industrial revolution, especially in terms of the living conditions of workers, and to provide a new moral order for modern society.

The term itself is French. It was created in 1834 to contrast with individualism, a favorite term among liberals but i that early on socialists saw as a symptom of moral decay. Right from its inception, socialism was contrasted with individualism and egoism, of the selfish and self-centered pursuit of wealth and power. Socialism proposed a new and better moral order, one in which the members of a society would care not only for themselves, but for one another. For the first decades of its existence socialism was less a motility with economic foundations than with ethical ones. It had economical arguments to brand, of course, but those arguments were based on moral or ethical claims.

By the eye of the nineteenth century, the discussion socialism came to be used more widely to describe several unlike movements than had hitherto been considered in isolation from 1 another. Their common factor was the thought that material goods should be held in mutual and that producers should keep the fruits of their labor, all in the name of a better, happier, more good for you community and, perhaps, nation. The abiding concern of early socialists was to address what they saw as the moral and social disintegration of European civilization in the modern era, too every bit to repair the rifts and meliorate the suffering of workers in the midst of early on industrial capitalism.

There was a major shift in socialism that occurred over the course of the century: until 1848, socialism consisted of a movements that shared a concern with the plight of working people and the regrowth of organic social bonds. This kind of socialism was fundamentally

optimistic – early socialists idea that most everyone in European gild would somewhen become a socialist once they realized its potential. Following the later work of Friedrich Engels, ane of the major socialist thinkers of the second half of the nineteenth century, this kind of socialism is often referred to as "utopian socialism." In turn, subsequently 1848, socialism was increasingly militant considering socialists realized that a major restructuring of society could not happen peacefully, given the forcefulness of both conservative and liberal opposition. The virtually of import militant socialism was Marxism, named after its creator Karl Marx.

3 early socialist movements stand out every bit exemplary of and then-called "utopian" socialism: the Saint-Simonians, the Owenites, and the Fourierists. Each was named afterwards its respective founder and visionary. The binding theme of these three early socialist thinkers was not only radical proposals for the reorganization of work, but the idea that economical competition was a moral problem, that competition itself is in no mode natural and instead implies social disorder. The Saint-Simonians called egoism, the selfish pursuit of individual wealth, "the deepest wound of mod social club."

In that, they found a surprisingly sympathetic audience among some aristocratic conservatives who were also afraid of social disorder and were cornball for the idea of a reciprocal prepare of obligations that had existed in pre-revolutionary Europe between the common people and the nobility. In plough, the early socialists believed that there was nothing inherent in their ideas threatening to the rich – many socialists expected that the privileged classes would recognize the validity of their ideas and that socialism would be a way to bridge the class split up, not widen information technology.

The Saint-Simonians, named after their founder Henri de Saint-Simon, were more often than not highly educated immature elites in France, many from privileged backgrounds, and many also graduates of the École Polytechnique , the most elite technical school in French republic founded by Napoleon. Their ideology, based on Saint-Simon'south writings, envisaged a society in which industrialism was harnessed to make a kind of heaven on earth, with the fruits of engineering going to feed, clothe, and house, potentially, everyone. They were, in a word, the starting time "technocrats," people who believe that technology can solve any problem. The Saint-Simonians did not inspire a pop movement, just individual members of the movement went on to accomplish influential roles in the French industry, and helped lay the intellectual foundations of such ventures as the cosmos of the Suez Canal between the Carmine Sea and the Mediterranean.

The Owenites were initially the employees of Robert Owen, a British manufactory possessor. He built a community for his workers in New Lanark, Scotland that provided health care, didactics, pensions, communal stores, and housing. He believed that productivity was tied to happiness, and his initial experiments met with success, with the New Lanark fabric factory realizing consistent profits. He and his followers created a number of cooperative, communalist "utopian" communities (many in the United States), simply those tended to fail in fairly brusque order. Instead, the lasting influence of Owenism was in workers system, with the Owenites helping to organize a number of influential early on trade unions, culminating in the London Working Men'due south Clan in 1836.

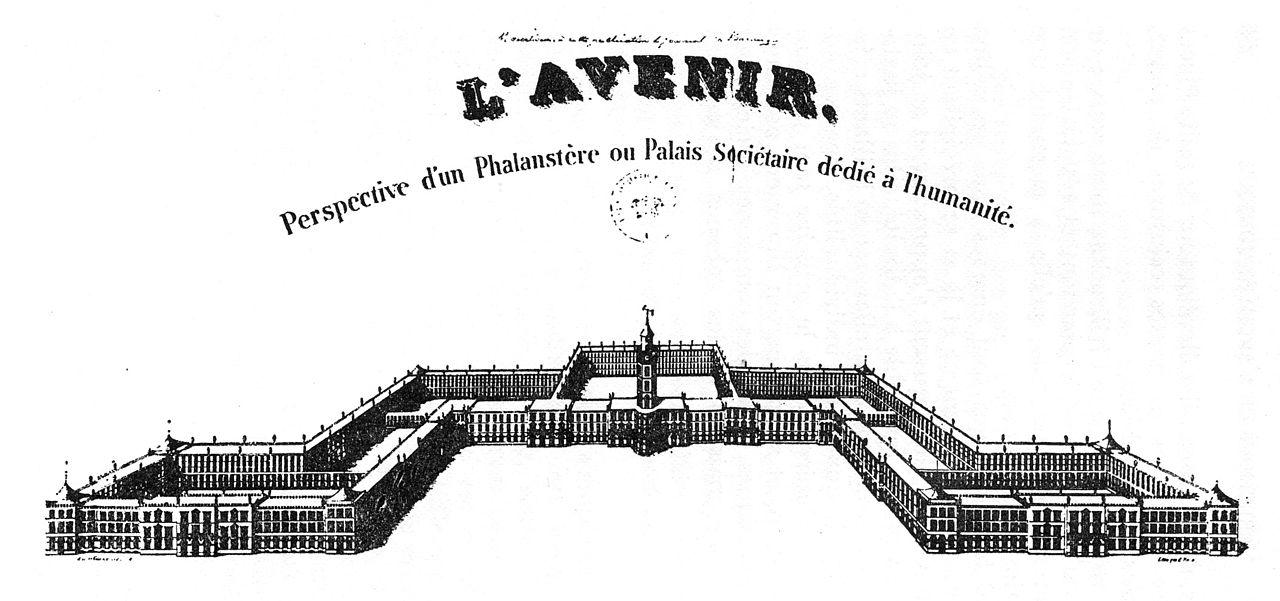

The Fourierists were function of a very peculiar movement, because their founder Charles Fourier was a very peculiar human being. Fourier, who may have been at to the lowest degree partially insane, believed that he had unlocked a "scientific discipline of the passions." According to Fourier, the reason that near people detested what they did to survive was that they were non doing the right kind of piece of work. There were 810 specific kinds of personalities in the world, each of which was naturally inclined toward a sure kind of piece of work. Thus, if 1,620 people (one man and i woman of each type) were to come up together in a community, and each did the kind of piece of work they "should" practice, perfect happiness became possible. For case, according to Fourier, murderers were but people who should have been butchers, and children should be trash collectors, considering they loved to play in the dirt. These planned communities would exist called "Phalanxes," after the fighting formations of ancient Greece.

Fourier was far more than radical than most other self-understood socialists. For one, he advocated complete gender equality and fifty-fifty sexual liberation – he was very hostile to monogamy, which he believed to be unnatural. Regarding spousal relationship every bit an outdated custom, he imagined that in his phalanxes children would exist raised in common rather than lorded over by their parents. Above and beyond forward-thinking ideas most gender, some of his concepts were a bit more puzzling. Among other things, he claimed that planets mated and gave nativity to baby planets, and that once all of humanity lived in phalanxes the oceans would turn into lemonade.

Practically speaking, the importance of the fourierists is that many phalanxes were actually founded, including several in the United States. While the more oddball ideas were conveniently set aside, they were still among the first real experiments in planned, communal living. Likewise, many of import early on feminists began their intellectual careers as Fourierists. For instance, Flora Tristan was a French socialist and feminist who emerged from Fourierism to practise important early work on tying the thought of social progress to female equality.

In general, the broad "Utopian" socialism of the 1840s was quite widespread leading up to 1848, it was peaceful in orientation, information technology was autonomous, it believed in the "correct" to work, and its followers hoped that the higher orders might join it. These early on movements also tended to cross over with liberal and nationalist movements, sharing a vision of more just and equitable laws and a more humane social social club in contrast to the repression all three movements identified with conservatism. Few socialists in this period believed that violence would be necessary in transforming society.

Considered in detail in the adjacent chapter, there was an enormous revolutionary explosion all over Europe in 1848. From Paris to Vienna to Prague, Europeans rose up and, temporarily as it turned out, overthrew their monarchs. In the stop, however, the revolutions collapsed. The awkward coalitions of socialists and other rebels that had spearheaded them soon cruel to infighting, and kings (and in France, a new emperor) eventually reasserted command. Socialists made important realizations following 1848. Republic did not pb inevitably to social and political progress, as majorities typically voted for established community leaders (often priests or nobles). Class collaboration was non a possibility, every bit the wealthier bourgeoisie and the nobility recognized in socialism their shared enemy. Peaceful change might not be possible, given the forces of order'southward willingness to utilise violence to achieve their ends. Russia, for instance, invaded Hungary to ensure the connected dominion of (Russia'southward ally at the fourth dimension) Habsburg Republic of austria. Later 1848 socialism was increasingly militant, focused on the necessity of confrontational tactics, even outright violence, to achieve a improve social club. Two mail-Utopian and rival forms of socialist theory matured in this period: state socialism and anarchist socialism.

The first, state socialism, is represented by the French thinker and agitator Louis Blanc. Blanc believed that social reform had to come from above. Information technology was, he argued, unrealistic to imagine that groups could somehow spontaneously organize themselves into self-sustaining, harmonious units. He believed that universal manhood suffrage should and would pb to a authorities capable of implementing necessary economic changes, primarily by guaranteeing piece of work for all citizens. He actually saw this happen in the French revolution of 1848, when he briefly served in the revolutionary government. There, he pushed through the cosmos of National Workshops for workers, which provided paid work for the urban poor.

In stark contrast was agitator socialism. A semantic betoken: riot ways the rejection of the country, not the rejection of all forms of social arrangement or even hierarchy (i.e. it is perfectly consistent for there to be an organized anarchist movement, fifty-fifty one with leaders). In the case of nineteenth-century anarchist socialism, there were two major thinkers: the French Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the Russian Mikhail Bakunin.

Proudhon was the author of a book entitled "What Is Holding?" in which he answered unequivocally that "property is theft." The very thought of ownership was vacuous and false to Proudhon, a conceit that ensured that the wealthy maintained their hold on political and legal power. Different his rival Louis Blanc, Proudhon was skeptical of the state's ability to effect meaningful reform, and after the failure of the French revolution of 1848 he came to believe that all state power was inherently oppressive. Instead of a state, Proudhon advocated local cooperatives of workers in a kind of "economical federalism" in which cooperatives would exchange goods and services between i another, and each cooperative would reward work with the fruits of that work. Simply put, workers themselves would proceed all profit. He believed that the workers would take to emancipate themselves through some kind of revolution, just he was non an advocate of violence.

The other prominent anarchist socialist was Mikhail Bakunin, a contemporary, sometimes friend, and sometimes rival of Proudhon. Briefly, Bakunin believed in the necessity of an apocalyptic, violent revolution to wipe the slate clean for a new order of gratuitous collectives. He loathed the country and detested the traditional family unit structure, seeing information technology equally a useless holdover from the past. Bakunin thought that if his contemporary lodge was destroyed, the social instincts inherent to humanity would blossom and people would "naturally" build a improve society. He was besides the great champion of the outcasts, the bandits, and the urban poor. He was deeply skeptical near both the industrial working course, who he noted all wished could exist eye grade, and of western Europe, which was shot-through with individualism, egoism, and the obsession with wealth. He ended up organizing big agitator movements in Europe'south "periphery," especially in Italia and Espana. By about 1870 both countries had large anarchist movements.

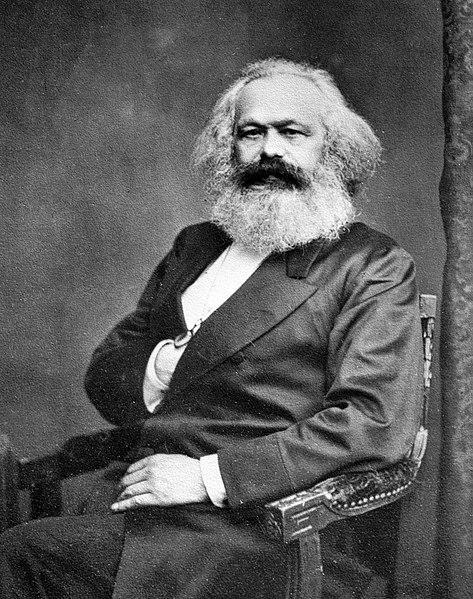

In the end, the about influential socialist was a German language: Karl Marx. Marx was built-in in 1818 in the Rhineland, the son of Jewish parents who had converted to Lutheranism (out of necessity – Marx'south father was a lawyer in conservative, staunchly Lutheran Prussia). He was a passionate and brilliant student of philosophy who came to believe that philosophy was but important if information technology led to practical change – he wrote "philosophers have only interpreted the globe in various means. The signal, still, is to alter it."

A journalist every bit a fellow, Marx became an avowed socialist past the 1840s and penned (along with his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels) the nineteenth century'due south well-nigh famous and influential socialist work,

The Communist Manifesto. Exiled to Corking Uk in the aftermath of the failure of the Revolutions of 1848, Marx devoted himself to a detailed analysis of the endogenous tendencies of capitalist economic science, ultimately producing three enormous volumes entitled, simply,Majuscule . The first was published in 1867, with the other two edited from notes and published by Engels after Marx's death. Information technology is worthwhile to consider Marx's theories in item because of their profound influence: past the middle of the twentieth century, fully a tertiary of the world was governed by communist states that were at least nominally "Marxist" in their political and economical policies.

All of history, according to Marx, is the history of class struggle. From aboriginal pharaohs to feudal kings and their nobles, classes of the rich and powerful had e'er driveling and exploited classes of the poor and weak. The world had moved on into a new phase following the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, even so, one that (to Marx) simplified that ongoing struggle from many competing classes to simply ii: the suburbia and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie were the ascension middle classes, the owners of factories and businesses, the bankers, and all of those with direct control over industrial production. The proletariat was the industrial working course.

Before this, the classes of workers in the pre-modern era generally had straight access to their livelihood: a small parcel of state, access to the common lands, the tools of their trade in the case of artisans. They had, in Marx'due south language, some kind of protected access to "the means of product," which could mean anything from some land, a plow, and an ox to a workshop stocked with a carpenter's tools. In the modern era, still, those rights and those tools were systematically taken away. The common lands were closed off and replaced with commercial farms. Artisans were rendered obsolete by the growth of industry. Peasants were pushed off the state or endemic plots so small their children had to await for work in the cities. The net event was, generally, that the class of workers who had "zippo to sell only their labor," the proletariat, grew.

At the aforementioned fourth dimension, the people who did ain property, "the bourgeoisie," were under pressure themselves. In the climate of the new commercialism, of unregulated markets and cutthroat competition, it was terribly like shooting fish in a barrel to fall backside and get out of concern. Thus, one-time members of the suburbia lost out and became proletarians themselves. The net effect was that the proletariat grew and every other conceivable class (including peasants, the owners of small shops, etc.) shrank.

Meanwhile, industry produced more than and more products. Every twelvemonth saw improvements in efficiency and economy in production, arriving at a terrific glut of products available for purchase. Eventually, at that place was simply too much out there and not plenty people who could afford to buy it, as one of the things about the proletariat, one of their forms of "alienation," was their inability to buy the very things they fabricated. This resulted in a "crisis of overproduction" and a massive economical collapse. This would be unthinkable in a pre-modernistic economic system, where the essential trouble a guild faced was the scarcity of goods. Thank you to the Industrial Revolution, nevertheless, products need consumers more than than consumers need products.

In the midst of one of these collapses, Marx wrote, the members of the proletariat could realize their common interests in seizing the unprecedented wealth that industrialism had made possible and using it for the mutual practiced. Instead of a scattering of super-rich expropriators, anybody could share in material comfort and freedom from scarcity, something that had never been possible before. That vision of revolution was very powerful to the immature Marx, who wrote that, given the inherent tendencies of capitalism, revolution was inevitable.

In turn, revolutions did happen, near spectacularly in 1848, which Marx initially greeted with elation merely to sentry in horror as the revolutionary momentum ebbed and conservatives regained the initiative. Subsequently, every bit he devoted himself to the assay of capitalism's inherent characteristics rather than revolutionary propaganda, Marx became more than circumspect. With staggering erudition, he tried to make sense of an economy that somehow repeatedly destroyed itself and nonetheless regrew stronger, faster, and more tearing with every business bike.

In historical retrospect, Marx was actually writing about what would happen if capitalism was immune to run completely rampant, every bit it did in the first century of the Industrial Revolution. The hellish mills, the starving workers, and the destitution and anguish of the manufacturing plant towns were all office of nineteenth-century European commercialism. Everything that could contain those factors, primarily in the grade of concessions to workers and state intervention in the economy, had not happened on a large scale when Marx was writing – merchandise unions themselves were outlawed in most states until the middle of the century. In turn, none of the factors that might mitigate capitalism's destructive tendencies were financially beneficial to whatever private backer, and then Marx saw no reason that they would ever come up about on a large scale in states controlled by moneyed interests.

To Marx, revolution seemed not merely possible but likely in the 1840s, when he was start writing about philosophy and economic science. After the revolutions of 1848 failed, however, he shifted his attending away from revolution and towards the inner workings of capitalism itself. In fact, he rarely wrote well-nigh revolution at all after 1850; his great workUppercase is instead a vast and incredibly detailed report of how England'south capitalist economic system worked and what information technology did to the people "within" it.

To boil it downward to a very simple level, Marx never described in adequate item when the cloth weather condition for a socialist revolution were possible. Beyond the vast breadth of his books and correspondence, Marx (and his collaborator Friedrich Engels) argued that each nation would have to reach a disquisitional threshold in which industrialism was mature, the proletariat was large and cocky-enlightened, and the bourgeoisie was using increasingly harsh political tactics to effort to keep the proletariat in check. There would accept to exist, and according to Marxism there always would be, a major economic crisis caused past overproduction.

At that point, somehow, the proletariat could rise up and have over. In some of his writings, Marx indicated that the proletariat would revolt spontaneously, without guidance from anyone else. Sometimes, such as in the 2d section of his early on work The Communist Manifesto , Marx alluded to the being of a political party, the communists, who would work to help coordinate and aid the proletariat in the revolutionary process. The lesser line is, all the same, that Marx was very skillful at critiquing the internal laws of the gratuitous marketplace in capitalism, and in pointing out many of its issues, but he had no tactical guide to revolutionary politics. And, finally, toward the stop of his life, Marx himself was increasingly worried that socialists, including self-styled Marxists, would try to stage a revolution "too early" and it would neglect or result in disaster.

In sum, Marx did not leave a clear picture of what socialists were supposed to do, politically, nor did he describe how a socialist country would work if a revolution was successful. This only mattered historically because socialist revolutions were successful, and those nations had to try to figure out how to govern in a socialistic way.

Social Classes

How much did European society resemble the sociological description provided by Marx? At first sight, nineteenth-century Europe seems more similar to how information technology was in before centuries than information technology does radically new – most people were still farmers, every country but Britain was still mostly rural, and the Industrial Revolution took decades to spread across its British heartland. That being said, European gild was undergoing pregnant changes, and Marx was right in identifying the new professional heart class, the bourgeoisie, as the agents of much of that change.

The term "suburbia" is French for "business class." The term originally meant, simply, "townspeople," just over time it acquired the connotation of someone who fabricated money from commerce, cyberbanking, or administration merely did not have a noble championship. The suburbia made up between 15% and 20% of the population of central and western Europe by the early 1800s. The male members of the bourgeoisie were factory owners, clerks, commercial and state bureaucrats, journalists, doctors, lawyers, and everyone else who brutal into that ambiguous class of "businessmen." They were increasingly proud of their identity equally "self-made" men, men whose fiscal success was based on intelligence, education, and competence instead of noble privilege and inheritance. Many regarded the quondam order equally an primitive throwback, something that was both limiting their own power to make money and society's possibilities of further progress. At the same time, they were defined by the fact that they did non work with their easily to make a living; they were neither farmers, nor artisans, nor industrial workers.

The growth of the bourgeoisie arose from the explosion of urbanization that took identify due to both industrialism and the breakup of the onetime social order that started with the French Revolution. Cities, some of which grew almost 1000% in the class of the century, concentrated groups of educated professionals. It was the center grade that reaped the benefits of a growing, and increasingly complex, economy centered in the cities.

While the bourgeoisie was proud of its self-understood sobriety and piece of work ethic, in contrast to the foppery and frivolity of the dignity, successful members of the centre course often eagerly bought as much land as they could, both in emulation of the nobles and considering the right to vote in most of western Europe was tied for decades to state-buying. In plow, nobles were wary of the middle grade, especially considering and then many conservative were attracted to potentially confusing ideologies like liberalism and, increasingly, nationalism, but over the course of the century the two classes tended to mix based on wealth. Old families of nobles may have despised the "nouveau riche," just they notwithstanding married them if they needed the money.

The bourgeoisie had sure visible things that defined them as a form, literal "condition symbols." They did not perform transmission labor of whatever kind, and insisted on the highest standards of cleanliness and tidiness in their appearance and their homes. In turn, all but the most marginal bourgeois families employed at least ane full-time servant (recruited from the working class and ever paid a pittance) to maintain those standards of hygiene. If possible, bourgeois women did no paid work at all, serving instead every bit keepers of the abode and the maintainers of the rituals of visiting and hosting that maintained their social network. Finally, the suburbia socialized in private places: individual clubs, the new department stores that opened in for the commencement time in the mid-nineteenth century, and the foyers of private homes. The working classes met in taverns ("public houses" or just "pubs" in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland), while conservative men and women stayed safely inside.

In addition, the members of the bourgeoisie were supposed to live by certain codes of behavior. In contrast to the sexual libertinage of the old nobility, bourgeois men and women were expected to avert extra-marital affairs (although, practically speaking, conservative men regularly took advantage of prostitutes). A bourgeois man was to live up to high standards of honesty and business organisation ethics. What these concepts shared was the fear of

shame – the literature of the time describing this social course is filled with references to the failure of a bourgeois to live upward to these standards and being exposed to vast public humiliation.

What about the nobility? The legal structures that sustained their identity slowly only surely weakened over the grade of the nineteenth century. Even more threatening than the loss of legal monopolies over country-owning, the officer corps of the army, and political status was the enormous shift in the generation of wealth abroad from land to commerce and industry. Relatively few noblemen had been involved in the early Industrial Revolution, cheers in large part to their traditional disdain for commerce, merely by the middle of the century it was apparent that industry, banking, and commerce were eclipsing state-ownership as the major sources of wealth. Too, the one thing that the suburbia and the working class had in common was a belief in the desirability of voting rights; by the cease of the century universal manhood suffrage was on the horizon (or had already come to pass, equally it did in French republic in 1871) in about every state in Europe.

Thus, the long-term pattern of the nobility was that it came to culturally resemble the bourgeoisie. While stubbornly clinging to its titles and its claims to authority, the nobility grudgingly entered into the economic fields of the bourgeoisie and adopted the bourgeoisie'south social habits likewise. The lines between the upper echelons of the suburbia and the bulk of the nobility were very blurry by the end of the century, equally bourgeois money funded old noble houses that still had admission to the social prestige of a title.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

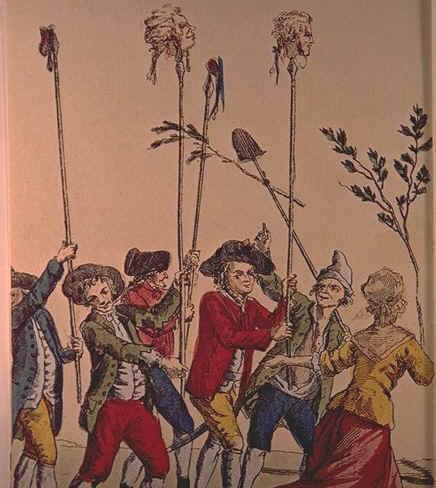

Heads on Pikes – Public Domain

Highland Soldiers – Public Domain

Marx – Public Domain

Top Hats – Public Domain

Source: https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/worldhistory/chapter/chapter-4-the-politics-of-the-nineteenth-century/

0 Response to "Leader Who Rose to Power After the French Revolution and Patron of the Arts"

Post a Comment